Transformative learning: For the many, not the few

The quickest path to public school improvement may be through a better understanding of successful and equitable schools. Equitable schools succeed with all students, not just those with the most skills or most privilege. A new study proves NewGlobe methods accelerate learning for all students, especially those predicted to struggle the most academically.

This study, led by Nobel-prize-winning economist Professor Michael Kremer, shows that NewGlobe’s methods produced better and more equitable learning outcomes among students randomly assigned to its schools. The Kremer et al. study randomly assigned students to a program in the NewGlobe portfolio. Students at NewGlobe-supported schools greatly outperformed their peers who attended either a government-funded public school or other private schools. During this two-year study, NewGlobe produced more than an additional year and a half of learning for pre-primary students and an additional year of learning for primary and middle school students.

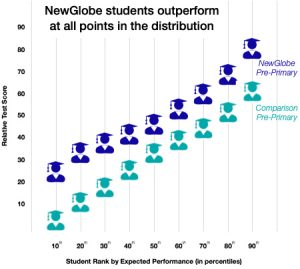

NewGlobe’s methods helped the least advantaged students most. NewGlobe supported students throughout the performance distribution and outperformed their peers in other schools.

NewGlobe’s methods helped the least advantaged students most. NewGlobe supported students throughout the performance distribution and outperformed their peers in other schools.

The differences were most stark at the Early Childhood Development (ECD) level (see chart). More than 80% of NewGlobe-supported students scored above the median (50th percentile) comparison student performance.

In a global school culture that tends to focus on and celebrate top scorers, it is rare to examine the performance of the lowest scoring students. Yet, these strong results suggest that all students irrespective of socioeconomic background can learn in good schools with sound instructional methods.

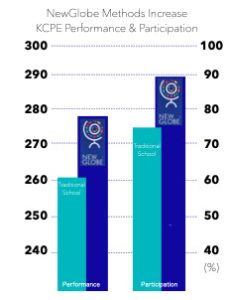

For the oldest students (Class 8), the Kremer study also found strong indicators of equity. On the high-stakes national exit exam – Kenya Certificate of Primary Education exam (KCPE) – NewGlobe supported students scored better and were more likely to take the exam (90% test-taking rate for NewGlobe supported students, compared to 75% test-taking rate for others). Compared to other schools, NewGlobe-supported schools had 60% fewer non-KCPE test takers. The test-taking rate was so different, with so many more students predicted to perform low who took the KCPE, that the study authors could only say that the large KCPE score differences between NewGlobe supported schools and comparison schools is a very conservative estimate of the actual performance differences. Since KCPE is the gateway to good secondary schools, these findings are more than just test scores. Higher KCPE scores and greater percentages of students taking the KCPE present expanded opportunities for students who otherwise might not continue their education.

scored better and were more likely to take the exam (90% test-taking rate for NewGlobe supported students, compared to 75% test-taking rate for others). Compared to other schools, NewGlobe-supported schools had 60% fewer non-KCPE test takers. The test-taking rate was so different, with so many more students predicted to perform low who took the KCPE, that the study authors could only say that the large KCPE score differences between NewGlobe supported schools and comparison schools is a very conservative estimate of the actual performance differences. Since KCPE is the gateway to good secondary schools, these findings are more than just test scores. Higher KCPE scores and greater percentages of students taking the KCPE present expanded opportunities for students who otherwise might not continue their education.

While these results were from a study in Kenya, where 57% of students attend secondary school, the problem of under-enrollment in secondary school exists throughout sub-Saharan Africa (44% secondary student enrollment, based upon 2019 WorldBank numbers). There is likely a great demand for schooling methods that build students’ capacity and confidence to continue their education past primary school.

The Kremer study also provides insight into the living conditions experienced by poor-performing students. In addition to assessing learning impacts by relative academic performance, Kremer et. al examined several household factors associated with relative wealth, such as having a dirt floor or mud walls, lacking electricity, or lacking a latrine, and comparably low parental income. It is unsurprising that it is difficult for students to thrive academically under such conditions, so much so that poor and low-performing students are often overlooked. It is quite surprising, however, that the Kremer et al. study found the greatest comparative advantages accrued to the least privileged NewGlobe-supported students.

That NewGlobe’s least privileged students outperform their similarly situated peers in other schools isn’t an accident. NewGlobe believes that all students can learn, and has designed pedagogy and lessons to meet students where they are academically and bring them to higher standards of performance. For example, “check and respond to every student’s work” is one of “the big four” teacher practices monitored closely by school leaders. Teachers learn to quickly stop at the student’s desk, provide feedback on whether the student is doing the task correctly, and move on to the next student. This simple practice signals to students that all count and all are expected to learn the lesson and perform the tasks. Since we know feedback improves performance and lower-income students and low performing students are less likely to receive feedback, ensuring all students receive the same amount of feedback immediately begins to close the performance gaps seen in typical school systems.

These strong learning gains, produced by the intentional application of strong methods within a context supportive of all students, are available to all. NewGlobe collaborates with many governments throughout sub-Saharan Africa and India to bring the exact same methods to public school students. NewGlobe’s internal measurement and evaluation studies report NewGlobe methods used within these public schools produce learning impacts very similar to Kremer et al. estimates for NewGlobe- supported schools in Kenya.

Kremer et al. suggest we understand the in-school factors that reverse inequities and build upon this learning to improve public schools. This study has taken tremendous steps towards learning which factors reverse inequities. The next step is to help public schools make the necessary changes, then continue to test, learn, and adapt until privilege is no longer a predictor of student learning outcomes.

The work to help public schools adopt more equitable practices is already underway. Public school transformation efforts built upon the model studied by Kremer et al. are being implemented in several countries, including India, Liberia, Nigeria, and Rwanda. In the next year NewGlobe will serve 2,000,000 students in government-funded public schools, using the same instructional technology, pedagogy, and school management blueprint used to deliver such equity of outcomes in the Kremer et al. study.

- Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112.